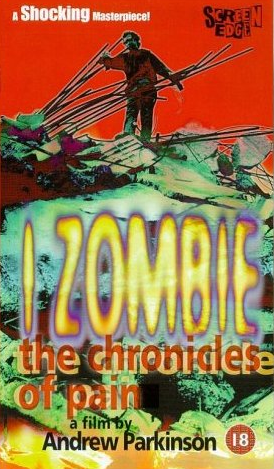

The first time I interviewed Andrew Parkinson was at the 9th Festival of Fantastic Films in September 1998 where he had just shown his debut feature, the extraordinary I, Zombie: The Chronicles of Pain.

![]() How long has it taken you to make this film?

How long has it taken you to make this film?

"I actually wrote the title and the opening paragraph for the film ten years ago. I then put it in a shoebox with about 25-30 other half-finished ideas. It sat around and vegetated away. I then spent the next six years making short super-8 films, the occasional pop video, the odd corporate film, then thought, 'Right, it's time to do a feature film. What have we got?' And I went through the old shoebox. It had been niggling away for some time, so I pulled it out and expanded the script into what became the shooting script. We started shooting that about four years ago."

Was that four years of shooting?

"What I did: I promised all the cast and crew it would take six months to make the film, which was my first lie. So we sat down, we shot the film, which took six months to shoot - like I said. I then spent another six, eight months editing the flm and putting the soundtrack on it. I looked at the film and I thought, 'This isn't quite working. It's not what I want it to be.' It was interesting, and most of the important points that are in the final film were all in there, but the structure wasn't there and it didn't pull the viewer in.

"We had a quick premiere of that film with a few of the people who worked on it. At the end they all sat there silently and made a few kind comments, then went home. I just went home and sat down and I just couldn't look at it for about two months. Then I thought, 'No, I spent all my money and all this time. We really have to pick this up by doing it again.' We'd probably lost about 18 months by this point, then we spent another year rewriting, reshooting and re-editing, by which point it was looking fairly reasonable. I was a lot more comfortable with what we'd got."

Was it tricky shooting new stuff so much later?

"It was a nightmare. But fortunately, the film itself was set over a two-year period. Had it been a film that takes place in a week or a day, I would have given up and left it. But fortunately that structure entitled us to go back and reshoot. In fact, if you watch the film, Ellen Softley the lead lady has about ten different hairdos throughout the film, most of them quite drastically different, but it doesn't jar at all when you watch it because of the structure. During that reshooting period, most of the stuff I put in balanced the zombie story up with Ellen's story. So you've got his story of how he has got worse and worse as a zombie, and her story of how she picks herself up and carries on with her life. They sort of intertwine a little bit, but not very much. It's just how they both resolve their own situations. At the end she's got over him, and at the end he's still living dead, lying in bed, can barely move."

![]() Having spent so long on it, at what stage did you decide it was finished?

Having spent so long on it, at what stage did you decide it was finished?

"Right. I think we got to a point where I was starting to lose people a little bit. This was probably around the three-year point! Which I think is quite fair and they were all entitled to be slightly unhappy with me, really. At which point I was working on a film for Dean Sipling who's also in the film. He's directing his own film now, called Think of England. It's a drama, a non-genre film, but what the hell. I was doing the camerawork on this film, and I'd had the idea of shooting some talking heads, just to pop in at various points in the film. After a day's shooting with him, I said, 'Okay, I know we're not shooting any more for I, Zombie, but just give me an hour of your time everybody.' And we shot those. I made a list of points that people had to discuss when they were interviewed, but that was it; it wasn't scripted. It was vaguely written, they read it once, and I said, 'Okay, tell me. It's been six months since you saw Mark. What's happened?' So you've got all these people trying to think of things to say and all these awkward pauses."

That worked very well.

"I can't say it was a clever move; it was a last desperate attempt. It's something Woody Allen seems to do quite a lot. There's a lot of his films where the story stops and you'll get one character interviewed, and then you're back into the story. I've seen this quite a few times I've thought, 'I wonder if he's trying to salvage this film here…' But when I cut those final bits in I just had this great sense of relief. They picked the film up at the various points where I thought it was dragging and dipping and wasn't working. At that point I knew it was finished and I thought, 'Okay.' Then I started to rewrite the score and to work on it with Tudor Davies who was the music producer on it. He also played all the keyboards. We then spent about six months working on the score and polishing it, and we spent about two months, on and off, mixing the final soundtrack.

"We had a friend who, while we were making the film, was actually building a broadcast quality dubbing studio in his double garage! He's since packed his day job in and runs it as a going concern. It's an extremely good dubbing suite. This was his first project. We had this sort of friendly rivalry. He said, 'Okay, you get your first dub free, and I won't know whether anything will work, so it doesn't matter. Here's the deal. If you come in and it breaks down after 12 hours and we lose everything, that's fine.' So we helped each other out there. We went back far more times than we should have done really, just polishing it, and we all became a bit perfectionist about the final mix. So after about six months on that, that was it. That was the finished tape. And that's the tape I started sending off to people."

You shot on 16?

"We shot on 16mm, transferred the 16mm onto Beta video, which is the current practice these days. Very few people cut on film. That gives you a reasonably good-looking cutting copy to work with on tape, which is far more convenient for showing people and sending things off. So that was what I did. I then took that final tape, and you can tape-grade these days. So the tape was repaired and some of the stuff was retransferred that I wasn't quite happy with. In fact I'm still going through the process, looking at the American release. I'm remastering the whole thing. But that was the final tape that we saw last night."

![]() And that's what Screen Edge are putting out?

And that's what Screen Edge are putting out?

"An absolutely huge release. It's funny. When I started making it, I dreamt of a few underground festivals showing it and perhaps the odd tape changing hands at a place such as this, but I never really thought it would get a release. There's a fairly underground-ish feel to it, for a horror film. For me it doesn't work as a mainstream horror film, so I was going for an edgy, sort of marginal feel to it."

Are you pitching it as a horror film? It's more of a character study.

"In fact a lot of the really good responses I've had from people who have watched it have been from women who say, 'What a great love story.' You've got a proper woman character in there and a normal bloke. He's a bit of a dork, and he's a student although he's too old to be student; he's disorganised and he's a bit of a prat, but at the end he's fundamentally a decent guy. And it's how he deals with all these things going wrong in his life. So for me, it's a study of isolation. It's a study of this guy going through some very strange changes in his life and how he copes with them."

What I liked was that the zombification was a necrotic disease, but not really supernatural.

"I wanted to stay away from all the supernatural stuff. In fact I wanted to stay away from trying to explain what he'd got too much. I didn't want, like in '50s movies, to say, 'Well, there's a been a bit of radiation about. Look at these zombies.' Or fertiliser that's brought the zombies out. I always felt that those scenes really let the films down, and I was more interested in what the characters were doing. He's a zombie, but he could well have any other disease that he couldn't have shown himself in public with. He could have AIDS or a very bad skin cancer or anything like that. But at the same time, I've always loved horror films; I like exploitation film; my heart is firmly in the gutter. So I wanted to make something that was a horror/exploitation film that also aspired to being a little bit more serious. A lot of films that I've liked that I've seen over the past five or six years have had that tone about them. That's what I was looking for."

Where did you find your cast?

"Most of the people involved with the film… shall I say we worked for the BBC? And we all came down to London at pretty much the same time from different parts of the country. We got to know each other. I'd been making short films for about ten years, which I carried on doing. Dean Sipling, who's an executive producer on the film and also in it, at the time came down and started running a drama group as well. Drama was something he'd always done. Tudor Davies, who was the sound recordist, who was also my flatmate - we shared the flat where the film was shot - the set! - he got involved with the film. But we all came along slowly as a film-making crew. I was going out and helping Dean out by doing lighting and production work on the plays, got to know Geoff, got to know Giles and Ellen. And in fact most of the other people who turn up in the film are from that drama group.

"It's a really nice way of working because you can get to know people over a six-month period and you don't have to give them some sort of crushing interview where you get them to do something stupid and ask them to leave and you don't give them the job. You know what people are capable of and what they're good at. So I thought, 'Yes, you'll do for this, you'll do for that, you'll do for that.' And they were all keen to get involved. Most people who work in semi-serious theatre love the thought of doing a bit of film. In fact London is a wonderful place to be to meet people like that; you're just overwhelmed with people wanting to get involved."

![]() The film rests a lot on the lead, Giles.

The film rests a lot on the lead, Giles.

"He was great. It's a funny role because he really doesn't speak very much. I think he's got about twenty lines of dialogue in the whole thing. The rest of the time he's either writhing around on the floor or eating people or staring mournfully into space."

Or having a sherman.

"Like you do! But yes, I'd made a short film just before I did I, Zombie with both Giles and Dean which worked really well and I thought, 'I like this guy'. It's a film called Reunion and it's set in a post-apocalyptic world where there are no women. Dean is this madman who waits for this delivery man who comes along with a case. Leaves the case, takes the money off him. Then we cut to him, with this inflatable doll that he's pulled out of the case. And he just has a quick session with the doll, and we leave him. Giles was the doll delivery man. There were very few of these dolls left. Strange film! Strange but I like it.

"So from working with him there and watching him work in the theatre, I thought, 'This guy's probably got what it takes.' When we started I was a little bit worried. But some of the first stuff that we filmed were some of the fits that he had on the floor at the start of the film. On a very, very rough carpet as well. And he just went for it 100%. I said, 'Okay. Well, you fall over and you have a fit then you get up and you eat somebody.''Okay, we'll give it a go.' And he just went for it and he was just fantastic."

Did you or he do any medical research into fits?

"Before I worked for the BBC I was a radiographer and I worked in the health service for ten years, so biology, physiology is something that absolutely fascinated me and still does. So I didn't really need to do any research. I had a pretty good background in looking at unpleasant diseases. I knew that I wanted his condition to look like something that could possibly happen. I didn't want him to go for a sort of distorted, Romero-esque zombie with the big forehead and all the rest of it. In fact, there's a scene in the film, a dream sequence where he's attacked by a zombie in the woods. A long-haired, really rotting-faced zombie. that was the original attack sequence that we used at the start of the film. I looked at it and I thought, 'It's too stylised, too over the top. We need to bring it down for it to be credible.' That ended up on the cutting room floor until late in the day when I thought, 'We could just do with something to end this dream scene. Oh yeah!' So it ended up back in the cut, which I was happy to see, after we shot it."

The make-up was also important.

"The make-up was really central to it for me. I've always loved horror films, the ones with good make-up and good effects, particularly good latex. I'm not really into digital effects; I really like a bit of latex and gore on the set. Even if it's badly done, to me it just looks wonderful! I was very lucky to get an 18-year old make-up guy called Paul Hyett who worked incredibly hard on the film, was very committed to it, on a minute budget. The proper cast effect, with moulded heads. He worked on it, he sculpted it, made the latex masks, put on the body parts, coloured them, put on the contact lenses. We did the whole works, and it was great. But in fact he looks at the film now and he cringes at various moments. He's distancing himself a little bit; he's now working in adverts and doing features and stuff. So he sees this occasionally ropy looking film that he worked on four years ago. But he was great."

![]() So what next for you?

So what next for you?

"At the moment I'm just writing a couple of films. I was thinking of starting one not many months away. I was going to leave it until after the Screen Edge release, just to get a bit more publicity, a bit more kudos. Some of the money's already in place. It'll be another little cheapy. I, Zombie was on 16mm; we might shoot it on super-16 which gives it slightly more sales potential in terms of blowing up to 35mm. But I'm happy to make another small scale film. I'm not interested in making any big jumps and going to LA and all the rest of it. I know the territory I'm comfortable with and we've just got to build on it. I've got some nice people interested again."

Are you taking I, Zombie around festivals?

"The problem with I, Zombie is I don't have a print of it which makes it a bit difficult for festivals. This is its first screening. There are one or two fantasy film festivals around the world that I'll be sending tapes off to as the year progresses. But it's one of those things where you start slowly and your PR starts working for you. The PR that Darrell did in Samhain really helped. It got people writing to me, which gives you a tremendous advantage really. As opposed to sending off a begging letter and a tape. So yes, it will be getting into more festivals and getting more publicity as the year goes on, hopefully."

How long has it taken you to make this film?

How long has it taken you to make this film?"I actually wrote the title and the opening paragraph for the film ten years ago. I then put it in a shoebox with about 25-30 other half-finished ideas. It sat around and vegetated away. I then spent the next six years making short super-8 films, the occasional pop video, the odd corporate film, then thought, 'Right, it's time to do a feature film. What have we got?' And I went through the old shoebox. It had been niggling away for some time, so I pulled it out and expanded the script into what became the shooting script. We started shooting that about four years ago."

Was that four years of shooting?

"What I did: I promised all the cast and crew it would take six months to make the film, which was my first lie. So we sat down, we shot the film, which took six months to shoot - like I said. I then spent another six, eight months editing the flm and putting the soundtrack on it. I looked at the film and I thought, 'This isn't quite working. It's not what I want it to be.' It was interesting, and most of the important points that are in the final film were all in there, but the structure wasn't there and it didn't pull the viewer in.

"We had a quick premiere of that film with a few of the people who worked on it. At the end they all sat there silently and made a few kind comments, then went home. I just went home and sat down and I just couldn't look at it for about two months. Then I thought, 'No, I spent all my money and all this time. We really have to pick this up by doing it again.' We'd probably lost about 18 months by this point, then we spent another year rewriting, reshooting and re-editing, by which point it was looking fairly reasonable. I was a lot more comfortable with what we'd got."

Was it tricky shooting new stuff so much later?

"It was a nightmare. But fortunately, the film itself was set over a two-year period. Had it been a film that takes place in a week or a day, I would have given up and left it. But fortunately that structure entitled us to go back and reshoot. In fact, if you watch the film, Ellen Softley the lead lady has about ten different hairdos throughout the film, most of them quite drastically different, but it doesn't jar at all when you watch it because of the structure. During that reshooting period, most of the stuff I put in balanced the zombie story up with Ellen's story. So you've got his story of how he has got worse and worse as a zombie, and her story of how she picks herself up and carries on with her life. They sort of intertwine a little bit, but not very much. It's just how they both resolve their own situations. At the end she's got over him, and at the end he's still living dead, lying in bed, can barely move."

Having spent so long on it, at what stage did you decide it was finished?

Having spent so long on it, at what stage did you decide it was finished?"Right. I think we got to a point where I was starting to lose people a little bit. This was probably around the three-year point! Which I think is quite fair and they were all entitled to be slightly unhappy with me, really. At which point I was working on a film for Dean Sipling who's also in the film. He's directing his own film now, called Think of England. It's a drama, a non-genre film, but what the hell. I was doing the camerawork on this film, and I'd had the idea of shooting some talking heads, just to pop in at various points in the film. After a day's shooting with him, I said, 'Okay, I know we're not shooting any more for I, Zombie, but just give me an hour of your time everybody.' And we shot those. I made a list of points that people had to discuss when they were interviewed, but that was it; it wasn't scripted. It was vaguely written, they read it once, and I said, 'Okay, tell me. It's been six months since you saw Mark. What's happened?' So you've got all these people trying to think of things to say and all these awkward pauses."

That worked very well.

"I can't say it was a clever move; it was a last desperate attempt. It's something Woody Allen seems to do quite a lot. There's a lot of his films where the story stops and you'll get one character interviewed, and then you're back into the story. I've seen this quite a few times I've thought, 'I wonder if he's trying to salvage this film here…' But when I cut those final bits in I just had this great sense of relief. They picked the film up at the various points where I thought it was dragging and dipping and wasn't working. At that point I knew it was finished and I thought, 'Okay.' Then I started to rewrite the score and to work on it with Tudor Davies who was the music producer on it. He also played all the keyboards. We then spent about six months working on the score and polishing it, and we spent about two months, on and off, mixing the final soundtrack.

"We had a friend who, while we were making the film, was actually building a broadcast quality dubbing studio in his double garage! He's since packed his day job in and runs it as a going concern. It's an extremely good dubbing suite. This was his first project. We had this sort of friendly rivalry. He said, 'Okay, you get your first dub free, and I won't know whether anything will work, so it doesn't matter. Here's the deal. If you come in and it breaks down after 12 hours and we lose everything, that's fine.' So we helped each other out there. We went back far more times than we should have done really, just polishing it, and we all became a bit perfectionist about the final mix. So after about six months on that, that was it. That was the finished tape. And that's the tape I started sending off to people."

You shot on 16?

"We shot on 16mm, transferred the 16mm onto Beta video, which is the current practice these days. Very few people cut on film. That gives you a reasonably good-looking cutting copy to work with on tape, which is far more convenient for showing people and sending things off. So that was what I did. I then took that final tape, and you can tape-grade these days. So the tape was repaired and some of the stuff was retransferred that I wasn't quite happy with. In fact I'm still going through the process, looking at the American release. I'm remastering the whole thing. But that was the final tape that we saw last night."

And that's what Screen Edge are putting out?

And that's what Screen Edge are putting out?"An absolutely huge release. It's funny. When I started making it, I dreamt of a few underground festivals showing it and perhaps the odd tape changing hands at a place such as this, but I never really thought it would get a release. There's a fairly underground-ish feel to it, for a horror film. For me it doesn't work as a mainstream horror film, so I was going for an edgy, sort of marginal feel to it."

Are you pitching it as a horror film? It's more of a character study.

"In fact a lot of the really good responses I've had from people who have watched it have been from women who say, 'What a great love story.' You've got a proper woman character in there and a normal bloke. He's a bit of a dork, and he's a student although he's too old to be student; he's disorganised and he's a bit of a prat, but at the end he's fundamentally a decent guy. And it's how he deals with all these things going wrong in his life. So for me, it's a study of isolation. It's a study of this guy going through some very strange changes in his life and how he copes with them."

What I liked was that the zombification was a necrotic disease, but not really supernatural.

"I wanted to stay away from all the supernatural stuff. In fact I wanted to stay away from trying to explain what he'd got too much. I didn't want, like in '50s movies, to say, 'Well, there's a been a bit of radiation about. Look at these zombies.' Or fertiliser that's brought the zombies out. I always felt that those scenes really let the films down, and I was more interested in what the characters were doing. He's a zombie, but he could well have any other disease that he couldn't have shown himself in public with. He could have AIDS or a very bad skin cancer or anything like that. But at the same time, I've always loved horror films; I like exploitation film; my heart is firmly in the gutter. So I wanted to make something that was a horror/exploitation film that also aspired to being a little bit more serious. A lot of films that I've liked that I've seen over the past five or six years have had that tone about them. That's what I was looking for."

Where did you find your cast?

"Most of the people involved with the film… shall I say we worked for the BBC? And we all came down to London at pretty much the same time from different parts of the country. We got to know each other. I'd been making short films for about ten years, which I carried on doing. Dean Sipling, who's an executive producer on the film and also in it, at the time came down and started running a drama group as well. Drama was something he'd always done. Tudor Davies, who was the sound recordist, who was also my flatmate - we shared the flat where the film was shot - the set! - he got involved with the film. But we all came along slowly as a film-making crew. I was going out and helping Dean out by doing lighting and production work on the plays, got to know Geoff, got to know Giles and Ellen. And in fact most of the other people who turn up in the film are from that drama group.

"It's a really nice way of working because you can get to know people over a six-month period and you don't have to give them some sort of crushing interview where you get them to do something stupid and ask them to leave and you don't give them the job. You know what people are capable of and what they're good at. So I thought, 'Yes, you'll do for this, you'll do for that, you'll do for that.' And they were all keen to get involved. Most people who work in semi-serious theatre love the thought of doing a bit of film. In fact London is a wonderful place to be to meet people like that; you're just overwhelmed with people wanting to get involved."

The film rests a lot on the lead, Giles.

The film rests a lot on the lead, Giles."He was great. It's a funny role because he really doesn't speak very much. I think he's got about twenty lines of dialogue in the whole thing. The rest of the time he's either writhing around on the floor or eating people or staring mournfully into space."

Or having a sherman.

"Like you do! But yes, I'd made a short film just before I did I, Zombie with both Giles and Dean which worked really well and I thought, 'I like this guy'. It's a film called Reunion and it's set in a post-apocalyptic world where there are no women. Dean is this madman who waits for this delivery man who comes along with a case. Leaves the case, takes the money off him. Then we cut to him, with this inflatable doll that he's pulled out of the case. And he just has a quick session with the doll, and we leave him. Giles was the doll delivery man. There were very few of these dolls left. Strange film! Strange but I like it.

"So from working with him there and watching him work in the theatre, I thought, 'This guy's probably got what it takes.' When we started I was a little bit worried. But some of the first stuff that we filmed were some of the fits that he had on the floor at the start of the film. On a very, very rough carpet as well. And he just went for it 100%. I said, 'Okay. Well, you fall over and you have a fit then you get up and you eat somebody.''Okay, we'll give it a go.' And he just went for it and he was just fantastic."

Did you or he do any medical research into fits?

"Before I worked for the BBC I was a radiographer and I worked in the health service for ten years, so biology, physiology is something that absolutely fascinated me and still does. So I didn't really need to do any research. I had a pretty good background in looking at unpleasant diseases. I knew that I wanted his condition to look like something that could possibly happen. I didn't want him to go for a sort of distorted, Romero-esque zombie with the big forehead and all the rest of it. In fact, there's a scene in the film, a dream sequence where he's attacked by a zombie in the woods. A long-haired, really rotting-faced zombie. that was the original attack sequence that we used at the start of the film. I looked at it and I thought, 'It's too stylised, too over the top. We need to bring it down for it to be credible.' That ended up on the cutting room floor until late in the day when I thought, 'We could just do with something to end this dream scene. Oh yeah!' So it ended up back in the cut, which I was happy to see, after we shot it."

The make-up was also important.

"The make-up was really central to it for me. I've always loved horror films, the ones with good make-up and good effects, particularly good latex. I'm not really into digital effects; I really like a bit of latex and gore on the set. Even if it's badly done, to me it just looks wonderful! I was very lucky to get an 18-year old make-up guy called Paul Hyett who worked incredibly hard on the film, was very committed to it, on a minute budget. The proper cast effect, with moulded heads. He worked on it, he sculpted it, made the latex masks, put on the body parts, coloured them, put on the contact lenses. We did the whole works, and it was great. But in fact he looks at the film now and he cringes at various moments. He's distancing himself a little bit; he's now working in adverts and doing features and stuff. So he sees this occasionally ropy looking film that he worked on four years ago. But he was great."

So what next for you?

So what next for you?"At the moment I'm just writing a couple of films. I was thinking of starting one not many months away. I was going to leave it until after the Screen Edge release, just to get a bit more publicity, a bit more kudos. Some of the money's already in place. It'll be another little cheapy. I, Zombie was on 16mm; we might shoot it on super-16 which gives it slightly more sales potential in terms of blowing up to 35mm. But I'm happy to make another small scale film. I'm not interested in making any big jumps and going to LA and all the rest of it. I know the territory I'm comfortable with and we've just got to build on it. I've got some nice people interested again."

Are you taking I, Zombie around festivals?

"The problem with I, Zombie is I don't have a print of it which makes it a bit difficult for festivals. This is its first screening. There are one or two fantasy film festivals around the world that I'll be sending tapes off to as the year progresses. But it's one of those things where you start slowly and your PR starts working for you. The PR that Darrell did in Samhain really helped. It got people writing to me, which gives you a tremendous advantage really. As opposed to sending off a begging letter and a tape. So yes, it will be getting into more festivals and getting more publicity as the year goes on, hopefully."