See also Part 1, Part 2 and Part 4.

In the basement (which, I note, also has a typewriter), Karl and Anna explore the room or maybe she shows him the room or something. Yes, I’m calling it a basement for the sake of sanity because it’s underneath a building except of course log cabins don’t normally have basements. Unlike the room upstairs, this is fully furnished - if a trifle dusty - with numerous hunting trophies on the walls. Karl lights a candle (not sure why as Anna has a torch and the room seems considerably less dark than upstairs) and they find a ballerina music box.

Okay, time out. I have to say something here. I absolutely fucking hate ballerina music boxes. They are the biggest cliché in cinema, certainly in horror and fantasy cinema. When have you ever actually seen a ballerina music box in real life? Exactly! The only thing worse than a ballerina music box is a ballerina music box in a room which has been kept exactly as it was when a child died/disappeared. One of the reasons why I consider The Silence of the Lambs to be such an over-rated piece of crap (not least because of the sequence where Hannibal Lecter escapes by employing world-class lock-picking skills never mentioned before or since and also by taking advantage of the police suddenly deciding to completely ignore their own advice and treat him as a low-risk prisoner with minimal guard, where was I? Oh yes...) One of the reasons that I hate Silence of the Lambs is because it employs this hoary old cliché: the child who disappeared or was killed and the bedroom left untouched all these years, just as she left it, and when Jodie Foster looks around she picks up a fucking ballerina music box which is Still Wound Up. I hate hate hate this cliché and I remain completely unable to fathom why people think that awful film is some sort of masterpiece.

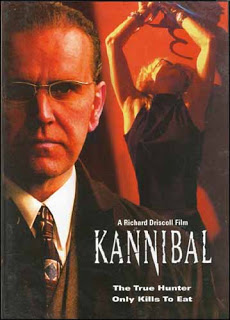

And if I hate Silence of the Lambs that much, you can imagine what I think about the cut-price Silence of the Lambs rip-off that is Kannibal.

Okay, breathe easy, rant over, waves on the shore, waves on the shore...

I am pleased to report that, although Evil Calls features a ballerina music box, it has not been kept by distraught parents. Well, actually, thinking about what I’m going to write here, maybe it has. Or maybe it hasn’t if he’s not their real father.

Anyway, while Karl and Anna look at the little doll twirling round we are treated to a brief SSF of the two Carney kids, dead but standing up and holding hands, then we jump back momentarily to the basement before another SSF, probably my favourite of all these flashbacks as it’s the most cinematic. As the Carney kids lie in bed, George Carney shows them the music box, the ballerina casting a dancing shadow onto the wall behind them, illuminated by the glow of a flame burning in the palm of Carney’s hand. It’s a lovely image. I don’t understand it, but at least it looks good.

This is followed by a shot of Anna, standing in a trance - there’s no sign of Karl - holding the music box which gradually fills with blood. This isn’t a lovely image, it’s just pretentious.

Another NSSF has Carney, wearing the check shirt that he wears in every scene except the ones in the hotel, walking through the hotel. In the washroom he meets a long-haired woman in a full-face mask and damn me if we don’t have that entire ‘mind the hot taps, aren’t you the manager?’ scene again. The lady in question wears the same as Norman and Rik did, only without a shirt (or bra). The other main difference here, apart from Carney’s own apparel, is that around the room are several naked or semi-naked young ladies, indulging in sexual antics either solo or in pairs.

By the by, do you know how you can tell the difference between pornography and erotica? Seriously. If a woman is completely naked it’s erotica. If she keeps her shoes on - that’s porn. These women, even the naked ones, all wear sexy heels. Oh, and they all have either masks or blindfolds. (Which is kind of curious, as masks and blindfolds are sort of the opposite of each other. A mask prevents people from recognising the wearer, whereas a blindfold prevents the wearer from recognising other people. I think it says something that by this point I’m more interested in pontificating on the social significance of blindfolds than concentrating on a washroom full of sexy, naked chicks.)

![]()

As the woman in the suit, bow-tie and white gloves goes through the now-familiar dialogue with a frightened-looking Carney, she pushes him to the floor then removes her jacket while the other women paw and grope both Carney and herself. Then she removes her mask and - it’s his wife! It’s... nope, we still don’t know her name. She’s still just ‘Mrs Carney’.

But the interesting thing here is the woman’s voice. Because according to the publicity, it’s Marianne Faithfull!

I say ‘according to the publicity’ but there is no mention of Faithful on the poster or the DVD sleeve or the House of Fear website, nor indeed is she credited on screen. But Rik Mayall, in his interview, says that the voice is Marianne Faithfull, the IMDB listing (which I wouldn’t normally trust but I’m fairly sure it has been updated by Driscoll or someone in his employ) says it’s Faithfull and the Wikipedia entry created after the film was released (which again I wouldn’t normally trust but I know for a fact this was written by Driscoll or someone in his employ) says it’s Faithfull.

When I first watched the film, when the cast list on the IMDB had no character names and before the Wikipedia entry was created, I doubted that this was Marianne Faithfull. It’s a plummy, posh English accent and I thought it might be Eileen - but it’s not, now that I listen a second time. Well well, Marianne Faithfull. An already strange cast list just progressed one notch further along the bizarre stick.

Now. Now things gets really weird. Now things start to make no sense at all. Oh, you might think that the previous 11,000 words (stick with me - nearly done!) described weird stuff that made no sense at all, but baby we’re just getting started and the night is young.

As George Carney lies on the floor of the men’s washroom in a posh hotel, groped by naked, blindfolded women while his semi-naked wife, also groped by naked, blindfolded women, tells him exactly the same thing that he was previously told by two blokes in the same room... a toilet cubicle door bursts open and gallons of crimson blood cascade out, flooding the room. This really is one of the most extraordinary images I have ever seen in a film. And what makes it even better is that the solitary bloke among all those hot, blindfolded, semi-naked, blood-splashed chicks wrote and directed this himself.

A Freudian would have a field day with this scene. Toilets, naked women, gushing blood: surely this is some sort of menstrual allegory, isn’t it? Well isn’t it?

As the blood flows, the scene switches to colour but only so that we can then, almost instantly, switch to another bloody SSF within this flashback. This is just some shots from Rik Mayall’s previous scene, with Chrissy Walken still doing his stuff on the soundtrack.

Now we watch Carney, wearing his check shirt (which he had taken off in the washroom), being roughly manhandled by masked/blindfolded waiters out in the main ballroom, with masked and blindfolded diners and dancers looking on (or not, I suppose). The waiters throw him into the washroom, which is now clean and empty, and he smashes a glass thing on the wall to get at a fire axe. With this he starts to smash down a cubicle door until he receives a tap on the shoulder, a polite cough and - there’s Rik asking: “Is there a problem with the handle, sir?”

Mayall then gets to spout some enigmatic tosh, once again showing himself to be the best thing in this film by a country mile, ending with the proclamation that, “If love is like a lightning bolt then betrayal - ahahaha! - betrayal is like a thunderclap!” At which point George Carney strangles him while fireworks burst from the urinals.

![]()

I really, really didn’t think I would ever type the phrase ‘fireworks burst from the urinals.’

All the above is sepia, leading straight into another bloody SSF of lightning hitting the ground near Vincent and Mrs Carney (the hell with it, I’m going to call her Doreen) as they walk through the forest towards the cabin. Not only are they unconcerned by this near-miss, I also think it’s curious that (a) it’s not raining and (b) the lightning hit the ground despite there being all these trees around. On account of, you know, it being a forest and everything.

Just when you thought that we had seen all the essential imagery we might need, we are presented with a colour shot of a teenage girl dressed as a ballerina and holding a crystal ball. (This may be Carney’s daughter, but as we have only previously seen her briefly in sepia with her hair done different, I couldn’t say for certain.) As we close in on the crystal ball we see, within it (and in sepia of course), Doreen tied to a chair with her mouth taped shut and George behind her. Before he slits her throat, he comes out with possibly the single worst line of dialogue I have heard this decade, expertly enunciated by Mr Driscoll in a display of acting wooden enough to suggest that his ideal role would be Pinocchio.

“You look beautiful tonight,” he tells Doreen (you see how much easier this has now become - I wonder what her real name is), “but like the four seasons, love changes, be it Summer, Autumn, Spring and of course Winter, the coldest time of the year. And like Winter - love grows cold!”

If I live to be one hundred I shall never be able to write dialogue as terrible as that. I mean, Christ, you would think he would at least get the seasons in the right order.

This is all intercut with an SSF of Vincent. Ah, now if you check right back at the start there was an SSF of somebody walking towards the cabin carrying a couple of fish and a net. This, it turns out, is Vincent and we see him finding Doreen, bleeding and dying, on the cabin floor. In a quick montage we get another shot of that female body impaled on horns (presumably it’s Doreen, there not being any other adult female characters in the flashbacks apart from the anonymous chicks in blindfolds), a recap of Carney sitting at his desk while blood pours through the walls and a brief shot of Anna still holding the blood-filled music box.

Then it’s daylight - finally. It’s the next morning and all the team are at the camp, including Victoria but excepting Steve. Rachel asks Anna to come with them because, “there’s nothing for you here,” but Anna says she can’t because, “I can’t explain.” Well, frankly neither can the audience, love. As Rachel, Lewis and James head off towards the Winnebago, carrying their flightcases but leaving their tents, Karl tells Anna that she made the right decision.

Ooh, ooh, here comes, your friend and mine, not seen him for ages, forgotten all about him but he’s back, it’s... the ravenringfirething!

At the Winnebago, Rachel, Lewis and James realise that Steve has the only set of keys. As the vehicle is clearly unlocked, presumably they are far enough away from civilisation to not have to worry about theft, so why weren’t the keys just left in the ignition? What was Steve planning to do with them in the middle of a forest, unlock some trees? More to the point, why has nobody said anything about Steve’s disappearance? And even more to the point, why is it now the middle of the night again? (Or still.) Is it because the journey between the vehicles and the cabin, which initially took two days and later took less than an hour has now averaged out at one day?

Back home, Gary (remember him?) looks at his monitor and sees a steadicam shot of the leaf-covered forest floor (apparently in daylight) so he tries unsuccessfully to contact Karl, then takes a look at another screen showing a map of the woods. Well, I say map but it’s actually just a green window with some evenly spaced tree graphics on it, plus some dots which presumably represent the team. But boy, wouldn’t that have been handy when Rachel was looking for Steve last night?

![]()

Gary calls Rachel but speaks with Lewis - the three friends are trekking back through the night-time woods - who angrily asks: “What can you see? ... What do you mean, you thought it was a set-up? People might be dying here and you’re worried about logging-on statistics!”

What is it that Gary thought was a set-up? Why might people be dying? Anyone got a clue? Anyone? Hello? As the camera whips around the trio at high speed for no reason, we cut briefly to a peaceful night-time shot of the camp, where the campfire still burns brightly, but only for a moment because here he comes again...

Ravenringfirething!

Rachel, Lewis and James find Steve’s dead body, although we still can’t see it’s Steve to be honest, but who else could it be? Lewis pulls from the corpse’s mouth a small... something. It might be a tile maybe. It looks ceramic, about an inch by inch and a half, with a black image of a raven and ‘The Raven’ written on it. No-one says anything and this is never referred to so let’s be honest here, this is an insert shot. It’s a pick-up which was filmed six years later in a desperate attempt to connect this film in some loose way to the Poe poem.

Because the truth is that, apart from this one briefly seen but unexplained and indecipherable thing, there are only three ways in which Richard Driscoll’s Evil Calls: The Raven is connected to Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Raven’. One is Christopher Walken actually reading the poem at various points, one is the ravenringfirething and the third is the witch’s name, Lenore. There are no actual ravens of any sort in this film apart from that arbitrary interstitial corvid: ravens are neither seen nor referred to, not even allegorical ones. No-one ever says the word ‘raven’ (apart from Walken). There’s no bust of Pallas, no-one says ‘nevermore’. Because when the bulk of this was shot it was Alone in the Dark and The Raven was a different putative Driscoll project.

“What about Karl and Anna?” says someone. “We’ve got to help them!” says someone else. Yes, what about them? Help them in what way? Are they in some danger? Apart from Steve’s corpse, there’s no indication of any danger and nobody seemed particularly worried that he was missing. In fact, nobody seemed to even notice, not even Rachel.

In another part of the wood, Karl (who has apparently left the camp for some reason) is looking for Anna when he stumbles across a stone Celtic cross, lying on the ground. He hefts it upright and as he does so we get a brief SSF of that witch being burned (in, let’s remember, the mid-19th century). After a brief cutback to Rachel who now seems to be, ahem, alone in the dark, Karl pulls the cross right out of the ground and a cloud of white smoke emerges from the hole. But how could it be stuck in the ground when he has only just lifted it up from where it was lying down among the undergrowth?

The action comes thick and fast now, and some might say that this makes it resemble the film-makers but that would be terribly unkind. There’s a jumble of brief, violent shots. A shotgun is loaded and then blasts Rachel’s head apart (a pretty neat effect). Some sort of hook slashes into Karl’s face and he is dragged, screaming, into the smoky hole from where he pulled the stone cross, his feet kicking ineffectually as he disappears under the earth. James is hit in the stomach with an axe, yet another victim of the off-screen murderer who has suddenly appeared from nowhere.

Lewis passes the previously seen scarecrow and stops. Staring in amazement he says, “It’s you!” before a chainsaw not only lops his head off but in the same movement sends it spinning through the air to land atop the scarecrow, knocking the scarecrow’s own head off in the process.

![]()

A scarecrow? In the ... wait, have I already done that bit?

A brief shot of an LP on a record player brings us to George Carney, wearing his check shirt but looking unkempt and unshaven. He is inside but it’s not clear where he is as there is a large stone fireplace and lots of brutal looking tools and weapons on the walls. As the only two rooms we have seen are the cabin and the cabin basement, and as this room is furnished and the walls clearly aren’t made of wood, my guess is it’s the basement although it looks nothing like the basement we saw before with the typewriter and the bookshelves and the hunting trophies.

Anna is pointing a pistol and we have to assume she’s pointing it at Carney although they never appear in the same shot. He runs over to one of the walls and slams his fist into it, smashing a gaping hole in the plasterboard. At this point the image, which has been a sort of blue-ish twilight, both inside and out, ever since Rachel, Lewis and James left the Winnebago, goes briefly into full colour. Carney pauses to light a cigar from a large, iron candelabra that we haven’t noticed before. Then he waves a meat cleaver about and cuts, I think, the head off an upside down body which is now sticking through the hole in the wall (although it wasn’t there when he made the hole). Actually, there is a scream which suggests this body is still alive.

But who’s this coming down the ladder? It’s Victoria Jordan! “Ladies and gentlemen,” says Carney, possibly to Anna who pops up occasionally in non-matching cutaways so is maybe supposed to be in the same room, “let me introduce to you - my little sister!”

The ladder confirms my suspicion that this room is the cabin basement even though it looks completely different to the basement that Karl and Anna explored. “But of course, Vincent,” he continues as he gives Victoria a big screen kiss, “you already know her.” And we see an SSF of Vincent Carney, walking backwards, superimposed over the body in the wall which is now rightside up and has its head attached, the unruly blonde hair suggesting it’s meant to be Vincent.

George says: “We never did like you, but that was our little secret.” Victoria holds up the missing part of the photo that Anna found and says, just in case we were in any doubt about the identity of the fur jacket-wearing woman in the picture: “That’s right - it’s me!”

Grinning like a loon, meat cleaver in hand, George Carney advances on the camera, which is presumably supposed to be Anna’s POV although the lack of any matching between shots of her and shots of him makes this less than certain. As the cleaver comes down...

...Anna sits bolt upright in bed. Karl draws the curtains to reveal a sunny day in New York and says they have a busy weekend ahead. Oh my Lord, she has gone back to that first morning! Is she doomed to live it all over again, endlessly repeating the same rubbish film? Will it make more sense the second, third or fourth time?

I very much doubt it.

![]()

The end titles start over a scratched, red-tinted effects shot of a gothic hotel, the one and only exterior of the building that we ever see. Then they cut to, and play out over, a photoshopped group shot of the cast and crew in evening dress (Mayall and Driscoll are very visible at the front). At the end of the titles we are given the blood-red caption ‘

The Raven 2: The Devil’s Disciple - coming soon’ and a momentary image of Carney and some sort of demon thing.

Seventy seven minutes after it started, Evil Calls is finally over.

All right: what just happened? What was the actual story here? Well, here’s what I can work out:

A century and a half ago a witch was burned at the stake in Harrow Woods, New England and cursed the place. A large hotel was subsequently built in Harrow Woods where the manager went insane and killed his family then later the hotel was purchased by horror writer George Carney. He took his family to a log cabin in the woods, presumably somewhere near the hotel that he had just bought but didn’t want to stay in. In this log cabin, which included a basement, Carney’s wife and brother Vincent killed his children (who were really Vincent’s children). Carney, driven to a jealous rage by the comments of the hotel manager’s ghost, murdered his wife and brother in return, then cleared up all the mess and disappeared. Two years later, on a date which is not only the anniversary of the Carney family’s disappearance but also the birthday of Anna (the only psychic in the group), five students and their tutor travel from New York to Harrow Woods. Their intention is to spend the weekend exploring the woods, trying to work out what happened to the Carneys, and this will all be broadcast live on the internet via a network of webcams positioned in the trees. Karl, the tutor (who is having an affair with Anna), has secretly invited along another psychic, Victoria, whom he has never met.

Something something something ravenringfirething.

The group split up and are brutally murdered one by one until only Anna is left - who discovers that George Carney is still alive and that Victoria is his sister. Then she wakes up and the whole thing starts again. (Room for one more on top…)

You can’t have failed to notice a big gap in the middle of that synopsis. A gap large enough to drive a Winnebago through. This is because everything from Victoria’s arrival to the quick montage of grizzly deaths at the end is Fucking Incomprehensible. Actually nearly everything up to and including Victoria’s arrival and nearly everything from the first grizzly death to the end of the credits is Fucking Incomprehensible too but at least there is some vague semblance of things happening, however nonsensical or contradictory they may be. It’s that middle act which just defies any ability to understand it. It seems to be a random jumble of images, not helped by a complete lack of consistency in terms of chronology and geography.

Did Richard Driscoll ever have a coherent script? It seems unlikely that the finished film is the one he started making back in 2002. There would be no reason for him to wait six years to film a handful of pick-ups and effects shots. So some of the picture’s incomprehensibility is almost certainly due to the enormous gap between principal photography and completion. I believe there was a finished version of Alone in the Dark (or at least a rough cut) all those years ago but I don’t know that for certain. What I do know is that Evil Calls more closely resembles a film derived from a garbled, confused, Fucking Incomprehensible script than a film derived from a coherent script which has been rendered Fucking Incomprehensible by post-production lasting the best part of a decade. What it resembles most closely however is a joint result: a Fucking Incomprehensible script which has, through extensive post-production, been rendered even less comprehensible. Fucking.

![]()

One thing that particularly intrigues me is the whole ‘hotel’ thing because, as I say, we only ever see this building under the end credits. There is no mention anywhere in the dialogue of a hotel yet a whole bunch of flashbacks are clearly set in an opulent establishment full of dinner tables and dancing couples. I surmised at the start of this review that the fake newspaper headlines under the opening titles might be the best clue to the movie’s plot and indeed they are. It almost seems as if the log cabin and the hotel are meant to be one and the same thing and that they are both, simultaneously and without contradiction, the building which exerts a powerful, supernatural influence on George Carney. It really looks like Driscoll wrote a story about a hotel then decided that the present day scenes would work better in a log cabin but never changed the flashbacks. I did wonder, as one does, whether the cabin had been built on the site of the hotel but it’s in the middle of the woods with lots of fairly large trees right next to it and no road anywhere near it. That’s just not a possibility (at least, in our dimension). In any case, the newspapers in the title sequence clearly state that a horror writer has bought a hotel. They don’t mention any cabin.

There is also no relevance whatsoever to George Carney being a horror writer (a dreamweaver, if you will - I’m sorry, I find it very difficult to write about the character without adopting a Garth Marenghi voice). It seems that he is a writer because Jack Nicholson in The Shining is a writer and he buys a hotel because Jack Nicholson in The Shining took his family to a hotel. There, I’ve said it. Evil Calls rips off The Shining even less subtly and more incompetently than Kannibal ripped off The Silence of the Lambs and its sequel. Very amusingly, the film’s Wikipedia entry (written by ‘InternetGore’ who must therefore be either Driscoll or someone working for Driscoll) claims that the film pays homage to The Shining (undoubtedly!), The Blair Witch Project (students filming themselves investigating spooky woods - fair enough) and Reservoir Dogs. I have watched this film twice, the second time taking notes that redefined for generations of film critics to come the concept of ‘excruciating detail,’ and I am completely unable to see any connection between this movie and Tarantino’s debut. There are no gangsters, no-one has colour-coded pseudonyms, no ear gets cut off, the soundtrack is completely devoid of Stealer’s Wheel songs. Seriously, help me out here folks. Has anyone seen this film and spotted a Reservoir Dogs influence? I will happily rewrite this paragraph if anyone can elucidate me.

But we don’t need to go to the Wikipedia entry for unanswered questions, there are plenty of those in the film. Actually, the end credits answer a few, most notably that she’s called Vivienne. Also, the ballerina is not Carney’s daughter and Vass Anderson plays ‘Prof. Jackson.’

Who? I mean… well, I just mean ‘Who?’

Thinking back through the plot (oh God, it’s like watching it all over again!) and eliminating all the other characters I can only surmise that this is the old guy with the PC, who never says anything and whose face we never see. Vass Anderson, who was in both The Comic and Kannibal, is an old, white guy and so that must be him - there are no other elderly people anywhere on screen apart from dear old Sir Norman (unless there’s a few extras at the back of the witch-burning mob). So that means the old guy is called Professor Jackson. If I recall correctly, when Gary and Karl were discussing how neither of them has actually seen Victoria before, Prof. Jackson was mentioned as the colleague who had recommended her. But that’s it - just one passing reference. As Victoria turned out to be trouble - possibly a supernatural entity, possibly a murderer, possibly not the real Victoria Jordan - are we to take this as evidence that Prof. Jackson set up the whole thing? Are they, indeed, related? Did he orchestrate this bewilderingly complex sequence of events as some means of disposing of his colleague Dr Mathers? If so, it’s the worst murder plan in cinematic history because even American cops should have no problem investigating the disappearance of six people during an event which was broadcast over the web.

![]()

And of course, Victoria doesn’t kill Karl, does she? Although she probably kills everyone else. That could be her blasting Rachel with a shotgun, that could be her lopping Lewis’ noggin off with a chainsaw (compare his “It’s you!” with her later “That’s right, it’s me!”), it could be her who gets James with an axe (poor old James, he had absolutely nothing to do; apart from criticising Lewis’ anachronistic taste in music in one short scene inside the Winnebago, he barely spoke). It is undoubtedly Victoria who kills Steve (in some unspecified way) and presumably she then leaves that little thing in his mouth. But Karl is dragged into the smoking pits of hell by a hook when he removes a stone cross that was blocking up the gateway to the netherworld. That couldn’t be Victoria’s doing. Could it?

Let’s face it, those final gore-shots - most of which were filmed during the Christmas 2007 shoot - make no sense. Why are the team killed? Why indeed do they split up? Why does not one single person mention Steve’s disappearance?

Then there’s the whole question of the relationship between George Carney and the woman calling herself Victoria Jordan. He says she’s his little sister. Look again at his dialogue in that final scene: “But of course, Vincent, you already know her. We never did like you, but that was our little secret.” Perhaps I’m missing something but unless Carney’s sister is a brand new character introduced two minutes from the end without explanation, the only other way to read that is that the person in the check shirt in the final scene, smoking a cigar and waving a meat cleaver around, is Carney’s son. Am I right? Is that how you read it? No-one else in this film has a sister (that we know of). There are no other siblings, certainly none who know Vincent Carney - and know him well enough to hate him. And if that was actually George Carney’s sister then it would be Vincent’s too.

But that can’t be Carney Jr all grown up because he was only a kid two years ago (as was his sister). Plus of course we saw them killed: the girl was drowned in the bath, the boy had his throat slit. But then again, we had an SSF of the two standing there, holding hands: she was dripping wet and his shirt was bloodstained. Are these their ghosts? After all, Victoria’s arrival was a supernatural affair. But even if they are ghosts they are still about thirty years too old! My brain is starting to itch.

Time and space. Time and space. Another dimension. It’s the only explanation. A dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind. Karl Mathers and his students just crossed over into… the Fucking Incomprehensible Zone.

Another thorny problem is working out in what decade the flashbacks take place. We are repeatedly told that the Carney family disappearance was two years ago (although we are also told that the Internetters have been doing this for both three and four years and that Saturday is the day after Monday). But when are the scenes in the hotel set? I’ve called them flashbacks - SSFs and NSSFs - but they’re really dream sequences or fantasy sequences I suppose, although they are still presented like old film. The palm-bedecked opulence of the place, the dinner suits and evening gowns, the obsequious staff in the washroom and especially the big band music suggest the 1940s, give or take a decade. But of course the nature of posh hotels is that they tend to look old-fashioned even today and there are still plenty of older couples who like to jive to a bit of big band boogie.

![]()

Is it significant that both the Carneys and the Internetters drive a car from around that era (possibly the same one)? Surely there must be some relevance in Lewis’ penchant for Glenn Miller and his ilk. But what? What does it all mean? Let’s face it, in a film which shows us people in 18th century clothes burning a witch and assures us that it happened in the mid 19th century, how can we use any on-screen clues to determine the era in which a scene takes place?

Continue to Part 4

![]() Shot over a considerable period of time, reflected in the changing hair-lengths of some actors, Full Moon Massacre incorporates some footage from an abandoned zombie project, mostly around the Jay/Kate romance. This shows up briefly towards the end when the young couple are cowering in a garage from Tom’s lupine monster and talk about the threat as “them”. But on the whole, considering that this film was shot mostly on the fly with no real script and incorporates parts of another, unrelated film, Lee has done an impressive job of making some sort of sense out of the whole thing.

Shot over a considerable period of time, reflected in the changing hair-lengths of some actors, Full Moon Massacre incorporates some footage from an abandoned zombie project, mostly around the Jay/Kate romance. This shows up briefly towards the end when the young couple are cowering in a garage from Tom’s lupine monster and talk about the threat as “them”. But on the whole, considering that this film was shot mostly on the fly with no real script and incorporates parts of another, unrelated film, Lee has done an impressive job of making some sort of sense out of the whole thing. Shot over a considerable period of time, reflected in the changing hair-lengths of some actors, Full Moon Massacre incorporates some footage from an abandoned zombie project, mostly around the Jay/Kate romance. This shows up briefly towards the end when the young couple are cowering in a garage from Tom’s lupine monster and talk about the threat as “them”. But on the whole, considering that this film was shot mostly on the fly with no real script and incorporates parts of another, unrelated film, Lee has done an impressive job of making some sort of sense out of the whole thing.

Shot over a considerable period of time, reflected in the changing hair-lengths of some actors, Full Moon Massacre incorporates some footage from an abandoned zombie project, mostly around the Jay/Kate romance. This shows up briefly towards the end when the young couple are cowering in a garage from Tom’s lupine monster and talk about the threat as “them”. But on the whole, considering that this film was shot mostly on the fly with no real script and incorporates parts of another, unrelated film, Lee has done an impressive job of making some sort of sense out of the whole thing.