Ben Shillito wrote was a credited writer on bothJust for the Recordand Dead Cert. In October 2010 he kindly agreed to an e-mail interview about his work on both movies.

![]() What is your background in writing, before your involvement with these two films?

What is your background in writing, before your involvement with these two films?

“I've been writing since I was old enough to hold a pen, and until recently almost everything I wrote was deeply odd. Reading back over some primary school compositions, an activity which my mother forces upon me almost every Christmas, I find my early writings near-Lynchian in their determined surrealism. Many of them feature cats in prominent roles, which illuminates a long-held pseudo-phobia of mine.

“By the age of eight I was writing Doctor Who scripts in my school note books (mostly revolving around Sabalom Glitz and carrot juice, but still featuring cats), and by the time I got to university I was earnestly churning out unpublishable novels practically every weekend, filling the halls of residence with the sound of secondhand-typewriter clatter. After graduation, I was set on an academic career (providing I could decide whether to do my PhD on Salman Rushdie or Discworld), but things went wrong when I developed (seemingly from nowhere) a crippling depression and had to be hospitalised, medicated and therapied back into the land of the living.

“Depression dragged on, as depressions are wont to do, until finally, in 2005, I decided that sitting in a shitty bedsit smoking roll-ups and pondering slashing my wrists was unprofitable, and that I should instead recast myself as a British answer to Kevin Smith, and I started reading about screen-writing, and devouring Faber & Faber's screenplays. While my first few efforts shared the earnestness of my written fiction, they were over-wrought and too padded with abject referentialism, deeply in debt (practically in slavery) to Lynch, Kubrick and Jarmusch, among others.

“It was a Sight and Sound article on Rodriguez and Tarantino that straightened me out, and got me thinking about film as an entertainment medium as well as a rarefied art form and message-delivery system. The next piece I wrote was a tight, twisty, 90-page noir thriller called Saltwater, and that script brought me to the attention (via various honourable intermediaries) of Steve Lawson.”

How did you get involved with Jonathan Sothcott and Steve Lawson?

“Steve was an aspirant when I met him. An actor building a career, using his substantial business background and connections to help finance a high-concept action thriller called The Rapture. Impressed by the script for Saltwater, Steve offered to help me make it and we shot a five-minute promo with Frank Harper and Danny John-Jules, but when The Rapture became a farrago to rival Heaven's Gate (but without the sole redeeming feature of a damn good script, which is what had saved Cimino's flabby opus), Steve and I parted company.

“For the next year I kept plugging away, managing to corral some actors and film students together to shoot a very low-budget quantum-physics essay called Strings, which ultimately suffered from the cutting of corners and didn't come together in the edit. It was while I was in the doldrums of trying to cut Strings that I heard from Steve again - he and producer Jonathan Sothcott had made the wise decision to walk away from The Rapture, and to focus instead on Just for the Record, a script based (in large part, at least) on Jonathan's experiences in the micro-budget film industry, and which seemed to speak to both of them at a point where they were reeling from The Rapture and somewhat embittered towards the business of show.

“The concept of the film, a screwball skewering of the pomp and pretensions of no-budget film-makers, was strong enough to attract some middle-drawer British talent, along with a lot of Steve and Jonathan's industry chums and chums-of-chums. With a start date fixed, and Steve having decided to direct the piece, I was asked to help Steve ‘tart up’ the script, which I duly did, under Steve's guidance.”

What was the Just for the Record script like when you were first shown it and what were you able to do with it?

“Since the project's original writer, Phil Barron, was still onboard, my involvement with the re-drafting was minimal. Steve and Jonathan would give their ideas, I'd try to map them out, and then everything was sent over to Phil, who did the actual work. Some of the more bizarre elements were reduced or removed (never ask about velcro-baby, that's my motto), but when the script came back it was 170 pages long and full of action set-pieces, including a running gag in which members of Andy Wiseman's documentary crew kept getting killed in front of him. (Along with velcro-baby, we never discuss the aggravated rape of Brad Pitt and Sylvester Stallone which fell about halfway through that draft.)

“It took a few mighty swings with an axe to repurpose that draft for the screen, but it was managed, and when we started shooting I was ‘associate producer and script editor’, which effectively means ‘secretary and punctuation-monkey’. As filming went on, more and more chums-of-chums were getting added to the cast, and I quickly took on the role of cameo-generator and on-set dialogue tweaker. My only substantive contribution to the script before shooting began was the creation and writing of Danny Dyer's character Derek LaFarge, but as time went on I was called upon almost every day to tuck myself away on set and ‘write a scene for [insert actor's name] as something like a [insert film-making role] with [insert illness, quirk or toilet problem]’.

“Although ultimately most of this stuff was cut, including a hilarious turn by Danny Midwinter as a faux-Jamaican porn-star and Jamie Foreman as a disco-dancing videographer, I was ultimately granted a writing credit in recognition of the LaFarge character and some dialogue for the likes of Sean Pertwee, Steven Berkoff and Billy Murray, although those characters were already in place in earlier drafts. Two lines remain of which I am proud: the karate sensei's Ro-wen-tah monk speech, and Alice Barry's final line about bottom love. Other than that, meh.”

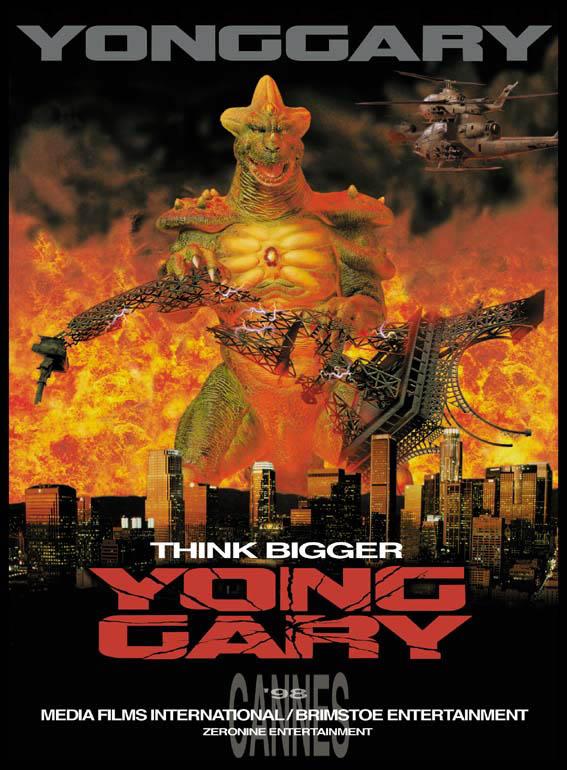

![]() What did you think when you first saw Metrodome's sleeve design for JFTR?

What did you think when you first saw Metrodome's sleeve design for JFTR?

“The JFTR sleeve came to my BlackBerry from Steve, forwarded from an original message from Jonathan. The design was attached as a jpeg, and the subject of the message was simply 'You're not going to believe this'. Suffice it to say, we didn't believe it. My response contained the word 'mendacious' - most other personnel used stronger language. Arguments followed. Many consumers were deceived. Enough said.”

The 'story/idea' credits of Dead Cert are totally unclear: what were the respective contributions of Lawson, Sothcott, Garry Charles and Nick Onsloe to the screenplay?

“The unclear credits are due to various contractual issues, and there is one thing in this answer that I have to skirt around for professional reasons. As frankly as I can put it - Garry Charles wrote a (very good) screenplay called Infernal, in which gangsters from the bare-knuckle boxing world go up against suave demon gangsters who own a fucked-up demon nightclub called Infernal, which the human gangsters must infiltrate to save one of their own after a thrown-fight arrangement goes sour. It was pacy, clever, and had some lovely moments, and it was sent to Steve and I at exactly the point we had begun discussing doing a vampire film, possibly with gangsters in it.

“Rather than risk ripping off Garry's work, we elected to option the script and repurpose it, changing the demons to vampires, and re-shaping the story. The characters of Frankham, Livienko et al were my work, and were developed over the course of several story conferences between myself, Steve and Nick Onsloe, an actor who is something of an encyclopaedia of bad ‘80s action and horror films. Between the three of us, we mapped out the shape of the story, then I went to work populating that framework with characters and scenes, working out the beats and scripting.

“After two quick drafts, we took it to Jonathan Sothcott, who brought his love of Hammer to the table, helping to develop the Livienko character's mythological underpinnings (a strain of Norse mythology from the poetic Edda, sadly lost from the finished film) and to construct a Van Helsing character in the form of Steven Berkoff's character, who was brain-stormed into existence over lunch with Mr Berkoff in a Docklands brasserie.”

What are the big differences between your original Dead Cert script and the shooting script, and between the shooting script and the finished film?

“The differences are many, and significant, but for the most part each revision was at least a partial improvement. Trying to write for a committee of people who all want story credit for their (very different) ideas is not easy, but in the actual writing I was left mostly alone, and then asked to revise elements for the next draft. In the very first draft, Freddy Frankham was a supporting character and Dennis Christian the lead, but the onus of the heroic sacrifice fell too heavily on Frankham, so their roles were inverted.

“The questions of Dennis's death and resurrection were batted back and forth a dozen times, and it was eventually settled on that he was addicted to Bliss, the Romanian party-drug, and that this contributed to his resurrection, partly to set up a plotline for a possible sequel. Sadly, this didn't make the cut, replaced instead with a shot of him being bitten by Dave Legeno's character during the central fight scene.

“A key change was the removal (at the producer's insistence) of any kind of subtext to the film. Originally, the Paradise/Inferno transition was meant to be far more significant, and the characters were to pass through an almost literal purgatory before deciding to act, with their understanding of the situation informed by the context of the Edda poem and of Berkoff's character's experience in the opening scene of the film (as scripted) - a mini-movie set in 1987, in which the hurricane hits Britain with the arrival of Livienko, and the Hiemdahl brotherhood are wiped out simultaneously in a surgically-precise strike by the vampires, with Berkoff's Kenneth Mason the sole survivor.

“This scene survives in several bitty flashbacks in the finished film, but its loss made several key thematic elements indistinct: Mason's relationship to femininity as a source of evil (his own daughter having been the vampire he killed in 1987 informing his relationship to the girls of the strip-club, and Frankham's pregnant wife), his loss of faith (the opening established him as a CofE vicar and academic) and the efficacy of religious symbols in dealing with vampiric evil in a secular world.

“As conceived, Eddie Christian's cunning criminality in the first act (in a lawless Paradise of his own making) was to be replaced by self-doubt in Purgatory (at his brother's funeral, and in several scenes in which he silently deals with his illness) and by a transformative re-emergence as a remorseless and still-cunning monster in the Inferno. Paralleled with the establishment of our key association of vampires with the aristocracy, and the suggestion that they are no better or worse than the rich feeding on the poor, Eddie Christian's journey was considered too subtextual, and heavily altered, with the explanation ‘Let's leave delivering messages to the Royal Mail.’

“As it stands, there is no reference to Eddie's illness until the middle of the third act, and the mental gymnastics required of the audience to process his earlier behaviour in light of this revelation are simply impossible to parse, especially given the context of this scene. To put it in Chekhovian terms, in the third act Eddie Christian fires a gun which the audience has not been shown in the first act, so the reverberations of the explosion are not felt on any dramatic level.

“The remaining changes, and the ones which I find most disappointing as a writer, were mainly on-the-fly alterations made by actors or creative personnel on set, which I personally feel never contributes anything to the film. In fact, actors' improvisations are almost always detrimental to the overall film, as they can end up critically compromising dramatic or thematic through-lines, or altering the meaning of an entire section of plot.”

What do you feel you have learned from your experiences on these two films?

“Looking at my work now, as compared to my work a year or two ago, a lot of what I have learned seems to be quite negative, but I don't personally regard these as negative experiences. My loathing for improvisation was solidified by the problems I saw it cause on Dead Cert, when entire scenes had to be re-thought on the fly because an actor changed something in another scene, but I think what I need to learn from that is not ‘restrict the freedom of actors’ but ‘make the script better’. When an actor has a problem with a line, it's as likely to be because it isn't written into the character properly as it is simply a matter of ego or showing off. Having said that, when an actor as good as Steven Berkoff or Dexter Fletcher comes in and doesn't change so much as a comma, then you know you must have done something right.

“I have learned a lot about character, and the importance of structure, and about the need for every line to be perfect. Outside of the professional lessons, I learned a lot about the British film industry and how things work (or rather, don't), and possibly got an insight into just why the Brit industry is in such a parlous state. But the main thing I have learned, and this is as true in film as it was in my previous, academic, career - Goldwyn was right. Nobody knows anything. But it's still fun.”

![]() What projects are you working on now?

What projects are you working on now?

“I have recently finished three scripts: a fairytale adventure called Hamelin (co-written with journalist Ben Mortimer), a rollicking ‘60s-style spy yarn called Sleeper Bid, and a very dark and twisted Poe adaptation called The Red Death. Sleeper Bid was a commission job, and is likely to go into production in the next 18 months, Hamelin is doing the rounds looking for a buyer, and The Red Death is possibly to be my directorial debut, maybe next Autumn or in 2012 (assuming the Mayans weren't right, in which case I'm completely wasting my time).”

What is your background in writing, before your involvement with these two films?

What is your background in writing, before your involvement with these two films?“I've been writing since I was old enough to hold a pen, and until recently almost everything I wrote was deeply odd. Reading back over some primary school compositions, an activity which my mother forces upon me almost every Christmas, I find my early writings near-Lynchian in their determined surrealism. Many of them feature cats in prominent roles, which illuminates a long-held pseudo-phobia of mine.

“By the age of eight I was writing Doctor Who scripts in my school note books (mostly revolving around Sabalom Glitz and carrot juice, but still featuring cats), and by the time I got to university I was earnestly churning out unpublishable novels practically every weekend, filling the halls of residence with the sound of secondhand-typewriter clatter. After graduation, I was set on an academic career (providing I could decide whether to do my PhD on Salman Rushdie or Discworld), but things went wrong when I developed (seemingly from nowhere) a crippling depression and had to be hospitalised, medicated and therapied back into the land of the living.

“Depression dragged on, as depressions are wont to do, until finally, in 2005, I decided that sitting in a shitty bedsit smoking roll-ups and pondering slashing my wrists was unprofitable, and that I should instead recast myself as a British answer to Kevin Smith, and I started reading about screen-writing, and devouring Faber & Faber's screenplays. While my first few efforts shared the earnestness of my written fiction, they were over-wrought and too padded with abject referentialism, deeply in debt (practically in slavery) to Lynch, Kubrick and Jarmusch, among others.

“It was a Sight and Sound article on Rodriguez and Tarantino that straightened me out, and got me thinking about film as an entertainment medium as well as a rarefied art form and message-delivery system. The next piece I wrote was a tight, twisty, 90-page noir thriller called Saltwater, and that script brought me to the attention (via various honourable intermediaries) of Steve Lawson.”

How did you get involved with Jonathan Sothcott and Steve Lawson?

“Steve was an aspirant when I met him. An actor building a career, using his substantial business background and connections to help finance a high-concept action thriller called The Rapture. Impressed by the script for Saltwater, Steve offered to help me make it and we shot a five-minute promo with Frank Harper and Danny John-Jules, but when The Rapture became a farrago to rival Heaven's Gate (but without the sole redeeming feature of a damn good script, which is what had saved Cimino's flabby opus), Steve and I parted company.

“For the next year I kept plugging away, managing to corral some actors and film students together to shoot a very low-budget quantum-physics essay called Strings, which ultimately suffered from the cutting of corners and didn't come together in the edit. It was while I was in the doldrums of trying to cut Strings that I heard from Steve again - he and producer Jonathan Sothcott had made the wise decision to walk away from The Rapture, and to focus instead on Just for the Record, a script based (in large part, at least) on Jonathan's experiences in the micro-budget film industry, and which seemed to speak to both of them at a point where they were reeling from The Rapture and somewhat embittered towards the business of show.

“The concept of the film, a screwball skewering of the pomp and pretensions of no-budget film-makers, was strong enough to attract some middle-drawer British talent, along with a lot of Steve and Jonathan's industry chums and chums-of-chums. With a start date fixed, and Steve having decided to direct the piece, I was asked to help Steve ‘tart up’ the script, which I duly did, under Steve's guidance.”

What was the Just for the Record script like when you were first shown it and what were you able to do with it?

“Since the project's original writer, Phil Barron, was still onboard, my involvement with the re-drafting was minimal. Steve and Jonathan would give their ideas, I'd try to map them out, and then everything was sent over to Phil, who did the actual work. Some of the more bizarre elements were reduced or removed (never ask about velcro-baby, that's my motto), but when the script came back it was 170 pages long and full of action set-pieces, including a running gag in which members of Andy Wiseman's documentary crew kept getting killed in front of him. (Along with velcro-baby, we never discuss the aggravated rape of Brad Pitt and Sylvester Stallone which fell about halfway through that draft.)

“It took a few mighty swings with an axe to repurpose that draft for the screen, but it was managed, and when we started shooting I was ‘associate producer and script editor’, which effectively means ‘secretary and punctuation-monkey’. As filming went on, more and more chums-of-chums were getting added to the cast, and I quickly took on the role of cameo-generator and on-set dialogue tweaker. My only substantive contribution to the script before shooting began was the creation and writing of Danny Dyer's character Derek LaFarge, but as time went on I was called upon almost every day to tuck myself away on set and ‘write a scene for [insert actor's name] as something like a [insert film-making role] with [insert illness, quirk or toilet problem]’.

“Although ultimately most of this stuff was cut, including a hilarious turn by Danny Midwinter as a faux-Jamaican porn-star and Jamie Foreman as a disco-dancing videographer, I was ultimately granted a writing credit in recognition of the LaFarge character and some dialogue for the likes of Sean Pertwee, Steven Berkoff and Billy Murray, although those characters were already in place in earlier drafts. Two lines remain of which I am proud: the karate sensei's Ro-wen-tah monk speech, and Alice Barry's final line about bottom love. Other than that, meh.”

What did you think when you first saw Metrodome's sleeve design for JFTR?

What did you think when you first saw Metrodome's sleeve design for JFTR?“The JFTR sleeve came to my BlackBerry from Steve, forwarded from an original message from Jonathan. The design was attached as a jpeg, and the subject of the message was simply 'You're not going to believe this'. Suffice it to say, we didn't believe it. My response contained the word 'mendacious' - most other personnel used stronger language. Arguments followed. Many consumers were deceived. Enough said.”

The 'story/idea' credits of Dead Cert are totally unclear: what were the respective contributions of Lawson, Sothcott, Garry Charles and Nick Onsloe to the screenplay?

“The unclear credits are due to various contractual issues, and there is one thing in this answer that I have to skirt around for professional reasons. As frankly as I can put it - Garry Charles wrote a (very good) screenplay called Infernal, in which gangsters from the bare-knuckle boxing world go up against suave demon gangsters who own a fucked-up demon nightclub called Infernal, which the human gangsters must infiltrate to save one of their own after a thrown-fight arrangement goes sour. It was pacy, clever, and had some lovely moments, and it was sent to Steve and I at exactly the point we had begun discussing doing a vampire film, possibly with gangsters in it.

“Rather than risk ripping off Garry's work, we elected to option the script and repurpose it, changing the demons to vampires, and re-shaping the story. The characters of Frankham, Livienko et al were my work, and were developed over the course of several story conferences between myself, Steve and Nick Onsloe, an actor who is something of an encyclopaedia of bad ‘80s action and horror films. Between the three of us, we mapped out the shape of the story, then I went to work populating that framework with characters and scenes, working out the beats and scripting.

“After two quick drafts, we took it to Jonathan Sothcott, who brought his love of Hammer to the table, helping to develop the Livienko character's mythological underpinnings (a strain of Norse mythology from the poetic Edda, sadly lost from the finished film) and to construct a Van Helsing character in the form of Steven Berkoff's character, who was brain-stormed into existence over lunch with Mr Berkoff in a Docklands brasserie.”

What are the big differences between your original Dead Cert script and the shooting script, and between the shooting script and the finished film?

“The differences are many, and significant, but for the most part each revision was at least a partial improvement. Trying to write for a committee of people who all want story credit for their (very different) ideas is not easy, but in the actual writing I was left mostly alone, and then asked to revise elements for the next draft. In the very first draft, Freddy Frankham was a supporting character and Dennis Christian the lead, but the onus of the heroic sacrifice fell too heavily on Frankham, so their roles were inverted.

“The questions of Dennis's death and resurrection were batted back and forth a dozen times, and it was eventually settled on that he was addicted to Bliss, the Romanian party-drug, and that this contributed to his resurrection, partly to set up a plotline for a possible sequel. Sadly, this didn't make the cut, replaced instead with a shot of him being bitten by Dave Legeno's character during the central fight scene.

“A key change was the removal (at the producer's insistence) of any kind of subtext to the film. Originally, the Paradise/Inferno transition was meant to be far more significant, and the characters were to pass through an almost literal purgatory before deciding to act, with their understanding of the situation informed by the context of the Edda poem and of Berkoff's character's experience in the opening scene of the film (as scripted) - a mini-movie set in 1987, in which the hurricane hits Britain with the arrival of Livienko, and the Hiemdahl brotherhood are wiped out simultaneously in a surgically-precise strike by the vampires, with Berkoff's Kenneth Mason the sole survivor.

“This scene survives in several bitty flashbacks in the finished film, but its loss made several key thematic elements indistinct: Mason's relationship to femininity as a source of evil (his own daughter having been the vampire he killed in 1987 informing his relationship to the girls of the strip-club, and Frankham's pregnant wife), his loss of faith (the opening established him as a CofE vicar and academic) and the efficacy of religious symbols in dealing with vampiric evil in a secular world.

“As conceived, Eddie Christian's cunning criminality in the first act (in a lawless Paradise of his own making) was to be replaced by self-doubt in Purgatory (at his brother's funeral, and in several scenes in which he silently deals with his illness) and by a transformative re-emergence as a remorseless and still-cunning monster in the Inferno. Paralleled with the establishment of our key association of vampires with the aristocracy, and the suggestion that they are no better or worse than the rich feeding on the poor, Eddie Christian's journey was considered too subtextual, and heavily altered, with the explanation ‘Let's leave delivering messages to the Royal Mail.’

“As it stands, there is no reference to Eddie's illness until the middle of the third act, and the mental gymnastics required of the audience to process his earlier behaviour in light of this revelation are simply impossible to parse, especially given the context of this scene. To put it in Chekhovian terms, in the third act Eddie Christian fires a gun which the audience has not been shown in the first act, so the reverberations of the explosion are not felt on any dramatic level.

“The remaining changes, and the ones which I find most disappointing as a writer, were mainly on-the-fly alterations made by actors or creative personnel on set, which I personally feel never contributes anything to the film. In fact, actors' improvisations are almost always detrimental to the overall film, as they can end up critically compromising dramatic or thematic through-lines, or altering the meaning of an entire section of plot.”

What do you feel you have learned from your experiences on these two films?

“Looking at my work now, as compared to my work a year or two ago, a lot of what I have learned seems to be quite negative, but I don't personally regard these as negative experiences. My loathing for improvisation was solidified by the problems I saw it cause on Dead Cert, when entire scenes had to be re-thought on the fly because an actor changed something in another scene, but I think what I need to learn from that is not ‘restrict the freedom of actors’ but ‘make the script better’. When an actor has a problem with a line, it's as likely to be because it isn't written into the character properly as it is simply a matter of ego or showing off. Having said that, when an actor as good as Steven Berkoff or Dexter Fletcher comes in and doesn't change so much as a comma, then you know you must have done something right.

“I have learned a lot about character, and the importance of structure, and about the need for every line to be perfect. Outside of the professional lessons, I learned a lot about the British film industry and how things work (or rather, don't), and possibly got an insight into just why the Brit industry is in such a parlous state. But the main thing I have learned, and this is as true in film as it was in my previous, academic, career - Goldwyn was right. Nobody knows anything. But it's still fun.”

What projects are you working on now?

What projects are you working on now?“I have recently finished three scripts: a fairytale adventure called Hamelin (co-written with journalist Ben Mortimer), a rollicking ‘60s-style spy yarn called Sleeper Bid, and a very dark and twisted Poe adaptation called The Red Death. Sleeper Bid was a commission job, and is likely to go into production in the next 18 months, Hamelin is doing the rounds looking for a buyer, and The Red Death is possibly to be my directorial debut, maybe next Autumn or in 2012 (assuming the Mayans weren't right, in which case I'm completely wasting my time).”

.jpg)