In 1999, shortly before the release of The Phantom Menace, SFX asked me to research and write an article about the original release of Star Wars in 1977. I spent a day combing through the archives of the British Film Institute, checking the facts in original trade mags and this was the result. (The one instruction I was given was that I had to start with a reference to the Ash album 1977.) Written as a look back at how things had changed in the intervening 22 years, this has now become a fascinating time capsule in its own right of a time just before the prequels opened, when hopes were high...

Accompanying the article were two box-outs on contemporary reviews and the film's UK release.

If a band released an album called 1956, on which the first sound was the whirring of Robbie the Robot from Forbidden Planet, you might think they were a bit eccentric. If the album was called 1963 and started with the sound of the TARDIS, you might think the band were a bit sad. But if a band (such as, say, the popular beat combo Ash) released an album called 1977, kicking off with the distinctive sound of a TIE fighter, it would not only be seen as acceptable, but actually be deemed cool and played to death in the SFX office. Which it is, and has been.

Because it’s Star Wars.

All of which probably doesn’t totally encapsulate the significance of George Lucas’ little space opera in the grand scheme of things, but it’s as good an example to start with as any.

Very simply, it is impossible to overstate the importance of Star Wars in the history of cinema, in exactly the same way that it is impossible to overstate the importance of the Beatles in popular music. Like the Fab Four, Lucas’ film was not only a watershed in its own medium, but sent ripples throughout the whole of popular culture which still lap on the shore to this day. Just as you can instantly tell if a record was made before or after the Beatles, you can instantly date any film (not just SF) to pre- or post-Star Wars. And in the same way that Decca famously turned down those lovable moptops (D'oh!), so Universal passed on the chance to make George Lucas’ second film (D'o-oh!!!). Fortunately, Alan Ladd Jr at 20th Century Fox had the perspicacity to see something in Lucas’ idea and gave him the backing he needed - and the rest, as they say, is history.

Now, it is not strictly true to say that nobody expected Star Wars to be a hit. Admittedly, when the film opened on 25 May 1977, George Lucas was in a diner across the street from the Chinese Theatre and wondered what the long queue was for (he probably assumed it was for Rocky, Annie Hall, or the Mohammed Ali biopic The Greatest). He and his wife were planning to be in Hawaii when the film opened and had forgotten that the actual premiere was on the Wednesday. But let’s face it: Lucas would have had an ego the size of the Death Star if he had thought, “I bet they’re going to see my film.”

However, when Screen International asked movie executives about their expectations for the coming year, five months before the film came out, Percy Livingstone (Managing Director, 20th Century Fox Great Britain) had this to say on his company’s line-up: “Who could fail to be impressed by a schedule that includes movies like Gary Kurtz’ and George Lucas’ Star Wars, a majestic visual experience of extra-ordinary worlds?” A letter in the same trade mag the following week said: “The big movie for me for 1977 will be 20th Century Fox’s spectacular science fiction epic Star Wars.” So there was some expectation of success, but obviously not of success on the scale that the film achieved. What there was none of was hype. No big press build up; nothing. The film’s release wasn’t buried, but neither was it particularly trumpeted. Certainly not to the extent that, say, The Greatest was.

And yet Star Wars was a hit literally from day one. Though the reviews were on the whole superlative, they only started to appear as the film opened and could not possibly have directly influenced its record-breaking opening weekend (neither could word of mouth, obviously). It can only be deduced that there was a huge unspoken need among the public for a film of this type, which nobody except Lucas, Ladd and co. had picked up on - and even then quite possibly only by accident.

Star Wars opened in 21 American cinemas and on its first day grossed $215,443 at a ticket price of $3-4 each. By the end of its first week, Star Wars was playing on 42 screens and had taken $2,898,347. One week later, playing at 45 cinemas, the takings had risen to $5.2 million; a fortnight after that, on 157 screens, $13 million. At the end of June, by which time the film was playing across America at 360 cinemas, the gross was $20.5 million, already nearly double the film’s cost.

Explaining the success of Star Wars would take more than a few pages, but the key seemed to be the way that every aspect of it blended the old and the new. The story and characterisation were of a sort that had fallen out of favour with film-makers and could only be caught in TV screenings of old movies from the ‘30s and ‘40s, yet the movie was not presented as anything retro, but as something bang up to date. The technology used to make the film included cutting edge, innovative techniques, yet it also employed seemingly outdated ideas such as Vistavision (running 35mm film sideways to gain greater definition).

Though Ben Burtt’s sound effects gave the film an aural ambience never heard before, and Dolby stereo was a new concept to many audiences, John Williams’ score was an unashamed return to the sort of symphonic film music which by 1977 had completely died out. Even before the soundtrack album’s release, 20th Century Fox Records were saying that they expected the LP to be “a very, very big one” and were pressing as many copies as they could.

And what of the merchandise? George Lucas certainly didn’t invent spin-off movie merchandise - just consider the enormous range of Mickey Mouse ephemera sanctioned by Walt Disney in the 1930s - but he reintroduced the concept, fully aware that there lay the source of much of his income. Under the headline “Star Wars Product Bonanza”, the Hollywood Reporter on 8 June predicted “Although there are no projected figures on how much money merchandising will bring in from Star Wars, the amount will be astronomical, and possibly the largest ever for a motion picture.”

For the ordinary punter, Star Wars was simply like nothing that had ever been seen before, like nothing that had ever even been imagined before. With 22 years of post-Star Wars imagery in our minds, it’s difficult to imagine/remember (depending on age) what science fiction was like before this film. There were undoubtedly some pretty good SF films made in the early- to mid-1970s; indeed, given how small the genre’s output was at that time compared to the post-Lucas deluge, the overall standard was probably higher. Films like Logan’s Run, Soylent Green, Silent Running, A Clockwork Orange and the Planet of the Apes sequels had (and retain) their own charm, but it was notable that the 1977 Worldcon did not award a Best Dramatic Presentation Hugo because nothing received enough votes (Star Wars romped home in 1978, of course.)

The overall trend was clearly Earth-based future societies, and pretty grim ones at that - as indeed in Lucas’ own THX 1138. Space operas - especially feel-good space operas - were scarce, and there was a very good reason for that. Take a look at Dark Star, released almost simultaneously with Star Wars. The eponymous spaceship zips into the screen, sits there, and zips out - because it couldn’t do anything else. Think of the Enterprise in the original Star Trek: almost always seen in orbit, and from the same angle. The Discovery in 2001 didn’t seem to be moving at all, which is very realistic but hardly thrill-a-minute stuff. So imagine what it was like to suddenly see spaceships that whooshed and whizzed and zoomed and went ack-ack-ack-ack at each other. This is what spaceships are supposed to do (actually it’s not, but never mind) but you never thought you would actually see them do it. Today, this sort of thing is seen constantly in Star Trek, Babylon 5 and whatever piece-of-crap-with-stock-footage-from- Battle-Beyond-the-Stars Roger Corman has managed to knock up this week, but in 1977 it was unique.

Suddenly, everyone wanted a piece of the sci-fi action. There were a few SF films already in production, notably Superman, Norman J Warren’s Prey, and two Disney flicks: Return from Witch Mountain and The Cat from Outer Space. But the market domination of Star Wars meant that studios around the world rushed through anything they could find that could be slotted into the space-based trend. The first two productions of note were the Italian Star Crash and the Japanese Message from Space, although one must admire the British entrepreneur who simply picked up a 1976 Hong Kong film set during the Korean War and rush-released it as Sky Wars! Not wanting to be left behind by their own success, Fox immediately gave the green light to Ridley Scott’s Alien. And by the end of June, the Hollywood Reporter was announcing that the second season of The Muppet Show would feature a weekly sci-fi serial called Pigs in Space. Star Wars had definitely arrived.

And once it had arrived, it stayed. The Star Wars trilogy created more instantly recognisable icons - names, images, characters and ideas - than any other film or films before or since. In fact, more icons than almost any other story, with the possible exception of the Bible. Can there be anyone under the age of about 50 who doesn’t know Princess Leia, Darth Vader, R2-D2, Jabba the Hutt, Yoda or the Millennium Falcon? Surely everyone recognises a lightsabre, or an X-wing, or an Ewok. You don’t know what a Wookiee is? Get out of here, man! Science fiction has created other widely recognised iconography, such as the TARDIS or Mr Spock, but these images took time to ingrain themselves on the public consciousness. Darth Vader and co. were known all over the world within weeks of Star Wars opening.

Above all, Star Wars established in the public consciousness an idea of what science fiction was: all dogfighting spaceships, rebels battling empires, eccentric robots and aliens with funny heads. For better or worse, when Joe Punter now thinks of 'sci-fi' he doesn’t imagine Doctor Who or Thunderbirds or The Day the Earth Stood Still or Dune or The Time Machine. He thinks of the Millennium Falcon.

At the same time, Star Wars created the concept of the 'event movie', or at least The Empire Strikes Back did, because people were looking forward to that film for three years. Even beyond the films, the Star Wars franchise has continued to break new ground. Before Timothy Zahn’s Heir to the Empire trilogy was published, spin-off novels were ephemeral paperbacks, often written by hacks or pseudonyms. Suddenly, hardback spin-offs by respectable authors were topping the New York Times bestseller list.

Even in the late 1980s, the closest the franchise ever came to the doldrums, when there had been no new film for several years and the novels had yet to appear, Star Wars and all it contained were still prevalent throughout popular culture. In books, on records, in other films, on TV and radio, in comics and magazines: reference to Star Wars was common currency. It was a shared experience not just for an entire generation, but also for everyone who was too young to see it in 1977/78, but caught it on TV or video.

Over the past few years, with the books, the comics, the Special Editions, and now the run-up to Episode One itself, interest has built up to fever pitch. Lucasfilm’s management of the publicity has been magnificent, just teasing us all enough to get us hooked, and then gradually increasing the momentum with more and more photos and interviews. If we’re not all screaming for The Phantom Menace the week before it premieres, it will only be because we will be catatonic with anticipation by then.

But therein lies the great question: can Star Wars hit the same note again? One generation on, will audiences go crazy for The Phantom Menace the way they went ga-ga for the first three films? At the most basic level: will Jar-Jar Binks become as famous as Chewbacca? You see, it’s all changed. No really, it has.

Here are some of the things that were around in 1977 and are now no more: 8mm films (Star Wars in your own home, drastically edited to 15 minutes!); eight-track cartridges (the Star Wars soundtrack in this format is now worth several pence); supporting films (The Empire Strikes Back played with the less-than-thrilling Paws in the Park - can anyone remember what they saw Star Wars with?); theatrically released pornography (it is unbelievable how much porn dominated the mainstream cinema trade in the late 1970s); ladies who stood at the front during the intermission and sold choc ices; the intermission; Saturday morning matinees. Oh, it were all fields around here…

And here are some of the things we have now that we we didn’t have then: home video; home computers; the internet; satellite TV; cable TV; digital TV; laserdiscs; CDs; CD-ROMs; DVDs; CGI, SFX; THX; multiplexes; and a 16-year wait between Star Wars films. All of these will have some sort of effect on how The Phantom Menace is released, and how it is perceived. Twenty-two years ago, the only film mags were shallow little publications, providing studio-sanctioned news to the dwindling hordes of obsessive film-fans (“UK cinema audiences reach all-time low,” reported Screen International in April 1977). The only specialist SF mags were the fledgling Cinefantastique and the last death throes of Famous Monsters. There was no large-scale, organised SF movie fan-base, and a visit to the cinema wasn’t the universal pastime which it is now or was in the 1950s.

There is much more expectation now - even more than there was for Empire or Jedi - and the new movie has a lot to live up to: not just in comparison with the original trilogy, but also against other films. Everyone is wondering: will the new Star Wars film make more money than Titanic? Maybe, maybe not. The awful thing is that, even if it does better than every other film ever made except Titanic, it will still be deemed to have failed in some way.

But The Phantom Menace cannot bomb, simply because of what it is. Think of how successful the Special Editions of A New Hope, Empire and Jedi were. When we filed out of the cinema after the very first UK preview of the revamped Star Wars in May 1997, the overall mood among journos and fans was: “Erm, was that it?” Yet all three films topped the movie charts around the world, and the only people who didn’t buy them on video the moment they appeared were those who were still recovering from spending £100 on the Star Wars Chronicles book. (And can you think of any other topic you could compile a book on which would sell out in weeks with a cover price of a century?)

So yes, we all bought the lovely boxed set of the Special Edition videos, even though most of us had bought the remastered originals which were released only a year or so before. (And some of us still had the original rental tapes which we bought for £80 in the early 1980s!) And we will all go and see The Phantom Menace as soon as it opens (in fact a lot of people will see it on bootleg video in the two months between the US and UK premieres; one of Lucasfilm’s few planning slip-ups). We will buy the books and the toys (and the computer games and the CDs and the duvet covers and the Thermos flasks…), and then we will probably go and see the film a second time, maybe a third.

And when Episodes Two and Three come out, we will do it all over again.

Because it’s Star Wars.

Now see the two box-outs:

Box-out 1: Contemporary Reviews

Box-out 2: Star Wars released

Accompanying the article were two box-outs on contemporary reviews and the film's UK release.

If a band released an album called 1956, on which the first sound was the whirring of Robbie the Robot from Forbidden Planet, you might think they were a bit eccentric. If the album was called 1963 and started with the sound of the TARDIS, you might think the band were a bit sad. But if a band (such as, say, the popular beat combo Ash) released an album called 1977, kicking off with the distinctive sound of a TIE fighter, it would not only be seen as acceptable, but actually be deemed cool and played to death in the SFX office. Which it is, and has been.

Because it’s Star Wars.

All of which probably doesn’t totally encapsulate the significance of George Lucas’ little space opera in the grand scheme of things, but it’s as good an example to start with as any.

Very simply, it is impossible to overstate the importance of Star Wars in the history of cinema, in exactly the same way that it is impossible to overstate the importance of the Beatles in popular music. Like the Fab Four, Lucas’ film was not only a watershed in its own medium, but sent ripples throughout the whole of popular culture which still lap on the shore to this day. Just as you can instantly tell if a record was made before or after the Beatles, you can instantly date any film (not just SF) to pre- or post-Star Wars. And in the same way that Decca famously turned down those lovable moptops (D'oh!), so Universal passed on the chance to make George Lucas’ second film (D'o-oh!!!). Fortunately, Alan Ladd Jr at 20th Century Fox had the perspicacity to see something in Lucas’ idea and gave him the backing he needed - and the rest, as they say, is history.

Now, it is not strictly true to say that nobody expected Star Wars to be a hit. Admittedly, when the film opened on 25 May 1977, George Lucas was in a diner across the street from the Chinese Theatre and wondered what the long queue was for (he probably assumed it was for Rocky, Annie Hall, or the Mohammed Ali biopic The Greatest). He and his wife were planning to be in Hawaii when the film opened and had forgotten that the actual premiere was on the Wednesday. But let’s face it: Lucas would have had an ego the size of the Death Star if he had thought, “I bet they’re going to see my film.”

|

| Percy Livingstone |

And yet Star Wars was a hit literally from day one. Though the reviews were on the whole superlative, they only started to appear as the film opened and could not possibly have directly influenced its record-breaking opening weekend (neither could word of mouth, obviously). It can only be deduced that there was a huge unspoken need among the public for a film of this type, which nobody except Lucas, Ladd and co. had picked up on - and even then quite possibly only by accident.

Star Wars opened in 21 American cinemas and on its first day grossed $215,443 at a ticket price of $3-4 each. By the end of its first week, Star Wars was playing on 42 screens and had taken $2,898,347. One week later, playing at 45 cinemas, the takings had risen to $5.2 million; a fortnight after that, on 157 screens, $13 million. At the end of June, by which time the film was playing across America at 360 cinemas, the gross was $20.5 million, already nearly double the film’s cost.

Explaining the success of Star Wars would take more than a few pages, but the key seemed to be the way that every aspect of it blended the old and the new. The story and characterisation were of a sort that had fallen out of favour with film-makers and could only be caught in TV screenings of old movies from the ‘30s and ‘40s, yet the movie was not presented as anything retro, but as something bang up to date. The technology used to make the film included cutting edge, innovative techniques, yet it also employed seemingly outdated ideas such as Vistavision (running 35mm film sideways to gain greater definition).

Though Ben Burtt’s sound effects gave the film an aural ambience never heard before, and Dolby stereo was a new concept to many audiences, John Williams’ score was an unashamed return to the sort of symphonic film music which by 1977 had completely died out. Even before the soundtrack album’s release, 20th Century Fox Records were saying that they expected the LP to be “a very, very big one” and were pressing as many copies as they could.

And what of the merchandise? George Lucas certainly didn’t invent spin-off movie merchandise - just consider the enormous range of Mickey Mouse ephemera sanctioned by Walt Disney in the 1930s - but he reintroduced the concept, fully aware that there lay the source of much of his income. Under the headline “Star Wars Product Bonanza”, the Hollywood Reporter on 8 June predicted “Although there are no projected figures on how much money merchandising will bring in from Star Wars, the amount will be astronomical, and possibly the largest ever for a motion picture.”

For the ordinary punter, Star Wars was simply like nothing that had ever been seen before, like nothing that had ever even been imagined before. With 22 years of post-Star Wars imagery in our minds, it’s difficult to imagine/remember (depending on age) what science fiction was like before this film. There were undoubtedly some pretty good SF films made in the early- to mid-1970s; indeed, given how small the genre’s output was at that time compared to the post-Lucas deluge, the overall standard was probably higher. Films like Logan’s Run, Soylent Green, Silent Running, A Clockwork Orange and the Planet of the Apes sequels had (and retain) their own charm, but it was notable that the 1977 Worldcon did not award a Best Dramatic Presentation Hugo because nothing received enough votes (Star Wars romped home in 1978, of course.)

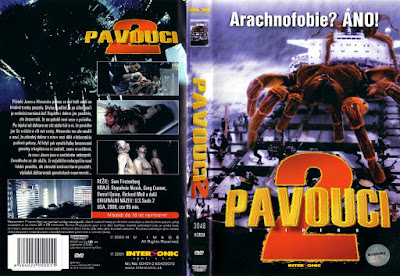

|

| 1978 Hugo Award |

Suddenly, everyone wanted a piece of the sci-fi action. There were a few SF films already in production, notably Superman, Norman J Warren’s Prey, and two Disney flicks: Return from Witch Mountain and The Cat from Outer Space. But the market domination of Star Wars meant that studios around the world rushed through anything they could find that could be slotted into the space-based trend. The first two productions of note were the Italian Star Crash and the Japanese Message from Space, although one must admire the British entrepreneur who simply picked up a 1976 Hong Kong film set during the Korean War and rush-released it as Sky Wars! Not wanting to be left behind by their own success, Fox immediately gave the green light to Ridley Scott’s Alien. And by the end of June, the Hollywood Reporter was announcing that the second season of The Muppet Show would feature a weekly sci-fi serial called Pigs in Space. Star Wars had definitely arrived.

And once it had arrived, it stayed. The Star Wars trilogy created more instantly recognisable icons - names, images, characters and ideas - than any other film or films before or since. In fact, more icons than almost any other story, with the possible exception of the Bible. Can there be anyone under the age of about 50 who doesn’t know Princess Leia, Darth Vader, R2-D2, Jabba the Hutt, Yoda or the Millennium Falcon? Surely everyone recognises a lightsabre, or an X-wing, or an Ewok. You don’t know what a Wookiee is? Get out of here, man! Science fiction has created other widely recognised iconography, such as the TARDIS or Mr Spock, but these images took time to ingrain themselves on the public consciousness. Darth Vader and co. were known all over the world within weeks of Star Wars opening.

Above all, Star Wars established in the public consciousness an idea of what science fiction was: all dogfighting spaceships, rebels battling empires, eccentric robots and aliens with funny heads. For better or worse, when Joe Punter now thinks of 'sci-fi' he doesn’t imagine Doctor Who or Thunderbirds or The Day the Earth Stood Still or Dune or The Time Machine. He thinks of the Millennium Falcon.

At the same time, Star Wars created the concept of the 'event movie', or at least The Empire Strikes Back did, because people were looking forward to that film for three years. Even beyond the films, the Star Wars franchise has continued to break new ground. Before Timothy Zahn’s Heir to the Empire trilogy was published, spin-off novels were ephemeral paperbacks, often written by hacks or pseudonyms. Suddenly, hardback spin-offs by respectable authors were topping the New York Times bestseller list.

Even in the late 1980s, the closest the franchise ever came to the doldrums, when there had been no new film for several years and the novels had yet to appear, Star Wars and all it contained were still prevalent throughout popular culture. In books, on records, in other films, on TV and radio, in comics and magazines: reference to Star Wars was common currency. It was a shared experience not just for an entire generation, but also for everyone who was too young to see it in 1977/78, but caught it on TV or video.

Over the past few years, with the books, the comics, the Special Editions, and now the run-up to Episode One itself, interest has built up to fever pitch. Lucasfilm’s management of the publicity has been magnificent, just teasing us all enough to get us hooked, and then gradually increasing the momentum with more and more photos and interviews. If we’re not all screaming for The Phantom Menace the week before it premieres, it will only be because we will be catatonic with anticipation by then.

But therein lies the great question: can Star Wars hit the same note again? One generation on, will audiences go crazy for The Phantom Menace the way they went ga-ga for the first three films? At the most basic level: will Jar-Jar Binks become as famous as Chewbacca? You see, it’s all changed. No really, it has.

Here are some of the things that were around in 1977 and are now no more: 8mm films (Star Wars in your own home, drastically edited to 15 minutes!); eight-track cartridges (the Star Wars soundtrack in this format is now worth several pence); supporting films (The Empire Strikes Back played with the less-than-thrilling Paws in the Park - can anyone remember what they saw Star Wars with?); theatrically released pornography (it is unbelievable how much porn dominated the mainstream cinema trade in the late 1970s); ladies who stood at the front during the intermission and sold choc ices; the intermission; Saturday morning matinees. Oh, it were all fields around here…

And here are some of the things we have now that we we didn’t have then: home video; home computers; the internet; satellite TV; cable TV; digital TV; laserdiscs; CDs; CD-ROMs; DVDs; CGI, SFX; THX; multiplexes; and a 16-year wait between Star Wars films. All of these will have some sort of effect on how The Phantom Menace is released, and how it is perceived. Twenty-two years ago, the only film mags were shallow little publications, providing studio-sanctioned news to the dwindling hordes of obsessive film-fans (“UK cinema audiences reach all-time low,” reported Screen International in April 1977). The only specialist SF mags were the fledgling Cinefantastique and the last death throes of Famous Monsters. There was no large-scale, organised SF movie fan-base, and a visit to the cinema wasn’t the universal pastime which it is now or was in the 1950s.

There is much more expectation now - even more than there was for Empire or Jedi - and the new movie has a lot to live up to: not just in comparison with the original trilogy, but also against other films. Everyone is wondering: will the new Star Wars film make more money than Titanic? Maybe, maybe not. The awful thing is that, even if it does better than every other film ever made except Titanic, it will still be deemed to have failed in some way.

But The Phantom Menace cannot bomb, simply because of what it is. Think of how successful the Special Editions of A New Hope, Empire and Jedi were. When we filed out of the cinema after the very first UK preview of the revamped Star Wars in May 1997, the overall mood among journos and fans was: “Erm, was that it?” Yet all three films topped the movie charts around the world, and the only people who didn’t buy them on video the moment they appeared were those who were still recovering from spending £100 on the Star Wars Chronicles book. (And can you think of any other topic you could compile a book on which would sell out in weeks with a cover price of a century?)

So yes, we all bought the lovely boxed set of the Special Edition videos, even though most of us had bought the remastered originals which were released only a year or so before. (And some of us still had the original rental tapes which we bought for £80 in the early 1980s!) And we will all go and see The Phantom Menace as soon as it opens (in fact a lot of people will see it on bootleg video in the two months between the US and UK premieres; one of Lucasfilm’s few planning slip-ups). We will buy the books and the toys (and the computer games and the CDs and the duvet covers and the Thermos flasks…), and then we will probably go and see the film a second time, maybe a third.

And when Episodes Two and Three come out, we will do it all over again.

Because it’s Star Wars.

Now see the two box-outs:

Box-out 1: Contemporary Reviews

Box-out 2: Star Wars released